A temporary wire left in place was the cause of the August accident

Informed Sources

This coming December will mark the 30th anniversary of the Clapham accident. Sir Anthony Hidden QC’s report, published the following September, threw British Rail’s Signalling & Telecommunications Directorate into shock.

Working on the ‘from loss of a nail’ causation principle, Sir Anthony showed how a concatenation of organisational failings had resulted in an overtired and undertrained technician not only failing to clip off a redundant (but still energised) wire but, in further breach of good practice, failing to wrap the exposed end in insulating tape. In retrospect, Sir Anthony’s 91 recommendations went beyond the essential issues contributing to that morning at Clapham, but that is the way of public inquiries.

For example, Recommendation 46 welcomed British Rail’s commitment to introduce Automatic Train Protection on a large percentage of its network. However, Sir Anthony remained concerned at the timetable proposed and recommended that ‘After the specific type of ATP system has been selected, ATP shall be fully implemented within five years, with a high priority given to densely trafficked lines’. Recommendation 47 required BR to report to the Railway Inspectorate ‘at six-monthly intervals on progress in implementing ATP’.

ORGANISATIONAL FAILINGS

While BR’s subsequent investigations suggested that the poor practices were limited to Southern Region’s Signalling and Telecommunications (S&T) organisation, the shortcomings revealed in management, training, supervision, working hours, testing plus past near misses – all these – destroyed the authority, and even more important, the confidence, of the top S&T engineers. Down the years, the great names in S&T engineering had always regarded themselves as the guardians of primary safety, now they were shown to be the cause of the problem, not the solution.

Change was immediate. Out went the Director S&TE and his deputy. The new DS&TE was Regional S&TE Ken Burrage from London Midland. And he threw himself and his team into the Augean stables with vigour. I remember going to see Ken Burrage at his Birmingham office for a briefing on the programme. The impression of radical change in action was all-pervading.

Out of all this came the current system of licensing and controls intended to ensure that another Clapham could never happen.

INFLUENCE

Privatisation further weakened the influence of the engineering disciplines. Railtrack’s first Chief Executive was noted for his disdain for engineers. Ken Burrage was among the first of the heads of departments to leave for somewhere more congenial. Come the Hatfield derailment there was not a senior civil engineer at headquarters to take a balanced view of the risk from gauge corner cracking – so the network was shut down.

Most recently, when electrification revived, there was no experienced senior engineer to pick up where they had left off with BR. Indeed, having ‘BR’ on your CV is not a positive factor within Network Rail. The result was the Great Western Electrification Programme, where experienced former BR old hands were called in only after starting from scratch had made electrification unaffordable

SHOCK

Why this potted history? Because I was not alone in being surprised at Network Rail’s apparently laid-back corporate non-reaction to the Waterloo derailment on 15 August last year. In my initial write-up (‘Informed Sources’, October 2017) I drew parallels with Clapham. The Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) interim report into the accident published in December shows a worrying litany of human failings of the kind Hidden was supposed to have prevented.

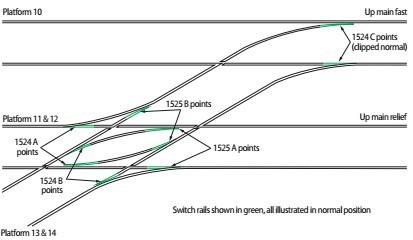

Figure 3 shows the arrangement of the points leaving platforms 11 and 12 at Waterloo. To recap, the 05.40 Waterloo to Guildford service was leaving platform 11 and, as far as the signaller and driver knew, the route was set for the train to run straight ahead onto the up main relief line. Having accelerated to 15mph the driver spotted that Points 1524A were sitting in the mid position between Normal and Reversed. The driver braked, but his train was routed towards the up main and sideswiped a rake of wagons parked on the adjacent line as a physical barrier between the work site and the working railway.

Since the signaller had set the intended route on his panel, and the driver had seen the platform end starter signal at green, the question immediately became ‘how could the safety interlocking be circumvented?’.

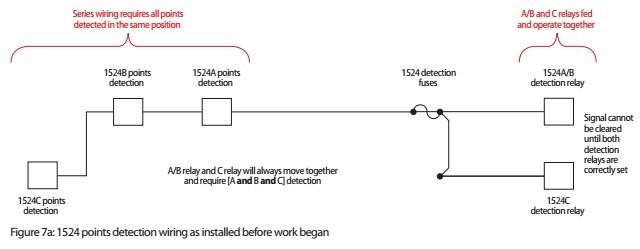

I hope that my signalling friends will forgive the following simplification, but to appreciate the seriousness of what happened we kneed to know how interlockings work. When each point end has been switched to set a route, contacts at the ends of the blades complete an electrical circuit. These contacts are in series – in a chain – so that if one has not closed and detected correctly, the current cannot get through.

Fig 7a shows this arrangement in simplified form. The detection relays at the right hand side of the diagram confirm to the interlocking that the points are set and locked as instructed.

Note that the 1524C detection relay was supplied by a feed off the main circuit. This was to be changed to a direct feed from 1524C as part of the Waterloo works.

TEST DESK

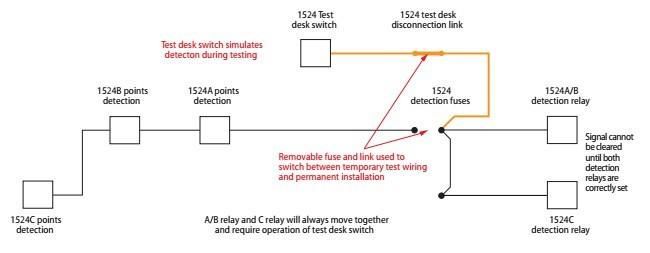

As an aid to commissioning, a test desk had been fitted which enabled signalling inputs to the interlocking to be simulated during commissioning. Clearly this could only happen when trains weren’t running.

At the start of the test, the testers would remove the fuses from the points’ operational circuits and insert a link from the test desk. Using the desk, testers could send signals simulating the state of points 1524 to the main interlocking. Fig 7b shows the test desk connected for use.

CHANGE

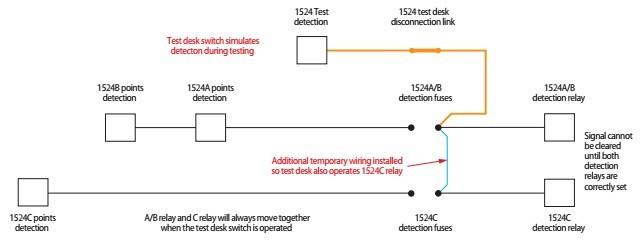

After the test desk had been installed, the need to move a lineside cubicle associated with the 1524 points resulted in the wiring being updated. 1524C now had its own unique circuit.

This had no effect on safety, as both point detection relays still had to be energised for the route to be set. However, the change did cause problems for users of the test desk, which could no longer simulate the signal to 1524C detection relay.

According to RAIB, to circumvent this restriction, over the weekend of 12/13 August 2017, ‘a temporary wiring modification was made in the relay room in an attempt to restore the correct operation of the 1524 points test desk switch’ (Fig 7e).

This modification, says RAIB, was not reviewed by a signalling designer and was left in place when the railway was handed back on the morning of 14 August. ‘Contrary to Network Rail standards, no test log or modification record has been found’. RAIB is still investigating the exact circumstances surrounding the installation of this temporary modification.

UNSECURED

Even more surely than the intermittent contact at Clapham, this undocumented impromptu link destroyed the integrity of the interlocking of Points 1524. If only A and B ends were detected, the signal could run via the rogue link and also energise C. And vice versa.

Now we come to how the points were left in mid-swing. Under the work plan for the weekend all the 1524 point ends were due to be been secured (clipped) in the Normal position. C was secured, A and B weren’t.

During the last night of the blockade, signalling testers were at work at Wimbledon Area Signalling Centre. One test sequence included setting 1524 points to reverse. It was known that they were supposed to be clipped to Normal, but this didn’t affect the test.

Test completed, 1524 points were set back to Normal. But A and B had been able to move as instructed.

Because of the rogue link, the three point ends now shared each other’s detection signals. So as A and B started to return to Normal they first lost their Reverse detection but, then, immediately, picked up the Normal detection from C which shut off power to the point motor.

And when, next morning, the route was set for the 05.40 to leave, the illegal link allowed all three ends of 1524 to be detected correctly on the signalling panel.

ONGOING

So that’s as much as we know, which leaves RAIB with much to investigate. Top of RAIB’s list are the design processes intended to ensure safe design of modifications made during the engineering work, the processes for identifying errors and the reasons why these processes were ineffective at Waterloo.

Then, what about the testing which could/should have identified the unsafe control system modification? And why did testing not throw up the error?

And, the most basic question, why were the A and B ends of 1524 points not secured as planned?

Then you get into all the Hidden issues: training, competence assessment, working hours and fatigue management for designers, checkers, installers and testers.

BASICS

‘The points had been left in this unsafe condition because they had not been identified as requiring securing by the team securing points during the works. Furthermore, no one had checked that all the points that needed to be secured during the works over the Christmas period had been. Route proving trains, a performance and reliability tool used to ensure the system was working correctly before running passenger services, had been cancelled.’ RAIB Report: Serious irregularity at Cardiff East Junction, 29 December 2016, October 2017

PRESSURE

Clearly, there will have been considerable pressure on all concerned to ensure that Waterloo reopened on time after the blockage and a lot of specialists will have been working long hours. Interestingly, in October last year RAIB published its report into a related type of incident following installation of a new track layout and signalling at Cardiff in December 2016.

When the new track layout was brought into use the driver of a departing train noticed that points in the route his train was about to take were not set in the correct position. He stopped his train. These points were redundant in the new layout, and should have been secured in readiness for subsequent removal. It transpired that two out of eight sets of newly redundant points had not been secured.

Had the driver not spotted the error and stopped, the train would have been diverted on to a line that was open to traffic. Worse, its presence would have gone undetected by the signalling system because axle counters had replaced track circuits.

RAIB’s report into Cardiff listed four ‘learning points’, including the need for Testers in Charge to be able to confirm that all redundant wiring and equipment has been checked. In the case of the unsecured points there had been a failure of communication. Compounding the error, route-proving trains, due to run at the end of commissioning works, had been cancelled.

That incidents such as Waterloo and Cardiff East are taking place, despite all those on site having the required competencies and licences, should be worrying.