Informed Sources

Captain Deltic gets in touch with his inner Greta

When the Rail Industry Decarbonisation Task Force published its initial report in January, it was roughly handled by my colleague Ian Walmsley (p38, March 2019 issue). My contribution was to explain the realities of replacing diesel engines in freight locomotives (p22, April 2019 issue).

In July, the final report was presented to the Minister for Rail – whoever that was at the time – and it made dispiriting reading. Well, not exactly dispiriting. The quote in the box threatened to trigger my early-onset, age-related irascibility.

Fortunately, Bill Reeve, the Director of Rail at Transport Scotland, in this very magazine last month, had provided the necessary medication. In Scotland they spell decarbonisation E-L-E-C-T-R-I-F-Y. Not only that, the assumption is that Scotland’s Seven Cities will be linked by electrified routes.

Anyway, having read the final report, what struck me, apart from the pleas on every other page for more research funding, was its lack of engagement with the real railway. Take this passage:

‘We estimate that there are, or shortly will be, about 3,000-3,300 diesel passenger vehicles that will need to be replaced, re-engined or converted, to decarbonise the railway. It should be possible to replace in excess of 2,400 vehicles with alternative low-carbon traction options such as hydrogen and battery trains. This will leave about 500-900 high speed vehicles where the most cost-effective option is likely to be to electrify the routes on which they run’.

ARE WIRES BEST?

‘Our focus throughout this report has been to challenge whether electrification is the best solution to achieve a net zero carbon railway in a manner consistent with delivering passenger benefits.’ Rail Industry Decarbonisation Task Force, July 2019

No mention of which vehicles. No mention of the train operators who run them. And the potential for 2,400 vehicles to be powered by fuel cells or batteries seemed frankly incredible. So I started a new decarbonisation spreadsheet.

CAVEATS

First, a health check. While what follows is a as accurate as I could make it, the results use various approximations for CO2 generation. Fuel consumption is based on the average of fleets, but does correlate with published figures for diesel fuel consumption and fleet miles.

According to the Decarbonisation Initial Report, passenger train diesel fuel consumption is 500 million litres a year. When burnt, this equates to 1.312 million tonnes of CO2. My spreadsheet comes up with 1.345 million tonnes. So within experimental error – as we used to say in A-level physics reports.

Also, remember that fleets are currently in transition with bi-modes, for example, replacing IC125s and diesel multiple-units. As a result, some of the CO2 outputs may be slightly overstated.

However, in terms of showing where the decarbonisation challenges are to be found, what follows is broadly accurate. Should any reader wish to make a similar analysis, I’d be only too happy to compare notes (e-mail: roger@alycidon.com).

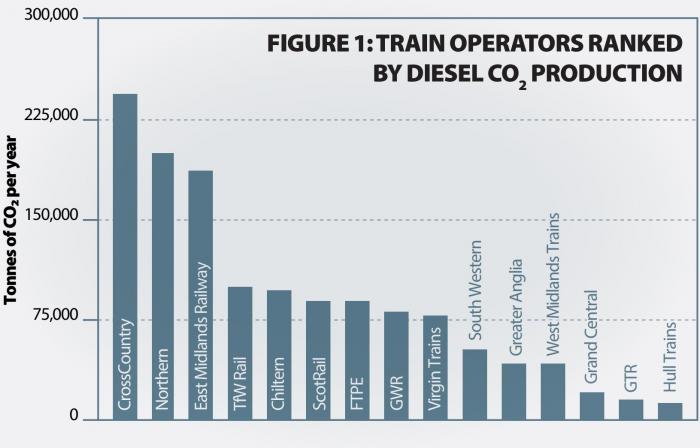

FLEETS

What I have done is list the individual fleets for each train operating company (TOC) running diesel powered trains. Next, I calculated the vehicle miles and applied the fuel consumption per vehicle mile to each fleet. This gives the annual fuel consumption of each fleet and hence the CO2 produced each year.

Note that I have not included bi-modes now in service because of the unknown break down between miles under the wires and diesel powered. I have also excluded LNER because the IC125 fleet should be retired by the end of the year.

Note, finally, that for simplicity I stick with simple CO2, rather than the more rigorous CO2 equivalent (CO2e).

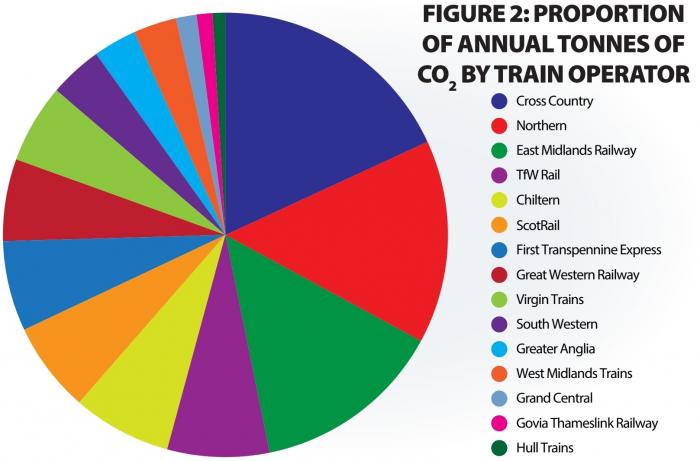

Figures 1 and 2 (overleaf) show the fruits of my labours in graphical form. They tell tells us pretty much what we would have expected.

In the top three TOCs, responsible for nearly 50% of emissions and each generating over 150,000 tonnes of CO2 a year, CrossCountry runs lots of heavy Voyager diesel-electric multiple-units. Much of the time these are running under the wires.

Northern, by contrast, has 11 fleets, running shorter distances, but cumulatively putting the franchise second in the CO2 generation league. This operator’s annual rolling stock fleet mileages highlight both the challenge and the opportunity: 34.7 million diesel powered versus 7.3 million electric traction.

East Midlands Railway, with its intensively used inter-city fleets of Class 222 Meridians and IC125s, is a smaller version of CrossCountry. And, if the government is serious about climate change, reinstating the

CO2E

Carbon dioxide equivalent or CO2e is a term for describing different greenhouse gases (GHG) in a common unit. For any quantity and type of greenhouse gas, CO2e signifies the amount of CO2 which would have the equivalent global warming impact. The main GHGs are carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and ozone.

Midland main line electrification to Nottingham and Sheffield is an early decision for the next administration.

NONSENSE

CrossCountry’s extensive diesel operation under the wires has been a self-evident nonsense from the start. Operation Thor – the unsuccessful proposal to turn the Voyagers into bi-modes by the addition of a pantograph-transformer car supplying the Alstom electric traction packages – was a missed opportunity.

I’m sure it would not be as easy as it sounds, but with Alstom trying, yet again, to re-enter the UK market, Thor 2.0 is surely worth consideration. No one knows what to do about CrossCountry’s rolling stock, which needs to be modernised and augmented.

A new fleet of bi-modes off the Newton Aycliffe production line would be a simpler and safer solution. One of the arguments for the bi-mode concept was that it could upgrade services while electrification was being extended and CrossCountry would be the classic example.

By the end of their 35-year service life, the CrossCountry bi-modes could be could be running under the wires from Aberdeen to Exeter or, ideally, beyond. Any contract would require provision in the specification for the diesel generator units to removed. And for residual operation beyond the wires you could get a reasonable number of last miles with seven tonnes or so of batteries in each powered car.

NORTHERN NETWORK

Of the ‘big three’, Northern is the greatest challenge for decarbonisation, as its large DMU fleet, responsible for over 80% of train mileage, shows. Trans-Pennine electrification is the starting point, but prioritising an electrification programme for this complex network is going to take a lot of work.

Here we have an example of the change of mindset required by decarbonisation. How do you reconcile the classic ranking of routes for electrification by business case against the environmental value of electrification in terms of its contribution to CO2 reduction?

This is clearly something Northern Powerhouse Rail should take under its wing and, dare I say it, is probably more important than the proposed new high-speed line. What we have to keep in mind is that relatively short sections of infill electrification can open the way to longer distances under the wires. This multiplier effect needs to be factored in to the decarbonisation electrification programme.

7% CLUB

Four TOCs are each currently responsible for around 7% of CO2 emissions.

Transport for Wales will make a useful contribution with the electrified Valleys Metro. And, of course, the drawings for Cardiff – Swansea will have to be rolled out again. A carbon-neutral ‘Gerald’ will provide a challenge for hydrogen fuel cell power.

Chiltern is a straightforward case of electrification, while Scotland has established its overall strategy, as already mentioned.

Similarly, TransPennine Express has already begun to go green with EMUs and bi-modes. And, of course, the advantage of the Nova 3 loco-hauled stock is that when the wires are up you can swap from diesel to electric traction and get more from your trains in terms of performance and reliability.

Something the proponents of discontinuous electrification on major routes should bear in mind is that it is a short-term fix which imposes handicaps on traction and rolling stock, and thus operation, in the long term.

NET ZERO

Both TOCs on 6% are already reducing their carbon footprint. Great Western will be all-electric on the London – Cardiff axis from early 2020 and, assuming the Class 769s can be made to work, will eventually move Networker Turbos to the West.

If we apply the Reeve Doctrine of linking major cities with electric services, extending the wires down the Berks and Hants in stages to Plymouth is a logical expectation. This may seem naïvely optimistic, but Rail Minister Jo Johnson’s qualified aspiration of removing ‘diesel only’ trains by 2040 has been overtaken by the Government’s commitment to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, signed in June this year.

Net zero requires any residual emissions to be balanced by schemes to offset an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Examples of such offsets include planting trees or carbon capture and storage.

This means that you could still have modern diesel engines in service in 2050, provided there were suitable offsets. But the Decarbonisation Task Force report makes an important comment on the latest change of target from the previous Government aspiration to achieve an 80% carbon reduction on 1990 levels by 2050.

Economic modelling work has suggested that to remove diesel-only passenger trains from the railway by 2040, and meet the former target, could have required 4,000 route kilometres of new electrification. Net zero carbon could be achieved with a further 250 route kilometres.

According to the Task Force Report, ‘if the outputs of this high-level modelling are proved correct in more detailed analysis, the marginal additional electrification is so limited that it almost makes sense on this basis alone to decide now on a net zero carbon target by 2050’.

Also on 6% is Virgin Trains, soon to be West Coast Partnership. Replacement of Voyagers with EMUs and bi-modes under the new franchise agreement will cut emissions substantially.

THIRD RAIL

Of the smaller contributors, South Western and Govia Thameslink Railway raise the issue of third rail electrification in-fills. Running DMUs between Ashford and Hastings is a self-evident nonsense. Nor is battery power a straightforward substitute, retaining the need for a dedicated fleet, plus extra weight and unknown battery life and replacement costs.

GTR and Network Rail’s devolved Southern Region need to heed the advice proffered to Macbeth by the second apparition and be bloody, bold and resolute in challenging the Office of Rail and Road’s veto on new third rail electrification. While I appreciate the concerns raised by maintainers that, apart from the 750 Volt live rail, cabling and other lineside equipment introduce trip and other hazards, we need to have a comprehensive risk assessment, producing some cold numbers on the likely risks of injury and death.

However, for extending electrification beyond, as opposed to within, the third rail network, overhead line electrification and dual-voltage traction is the obvious solution. As a thought exercise, readers might like to ponder a net zero solution for Waterloo Exeter.

FREIGHT

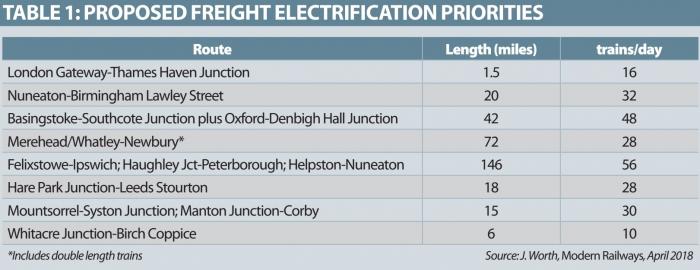

Way back in the April 2018 Modern Railways, Julian Worth made a powerful case for electrifying the freight network. Table 1 (p27) shows his proposed list of electrification schemes.

Mr Worth argued that this 320 miles of electrification would allow around 250 freight trains a day to be electrically hauled. This would represent almost all automotive and intermodal services plus two-thirds of construction trains.

And, of course, electrification would allow passenger services using these routes to retire diesel multiple-units. For the railway, net zero by 2050 is a huge opportunity both for the country and the industry. The real challenge, which no-one wants to talk about, is decarbonising road haulage.

I say ‘no one’, but the Decarbonisation Task Force was clear that with no low or zero carbon alternative to diesel for road haulage, rail ‘has a unique opportunity to offer low carbon freight transportation if greater use can be made of existing and future electrification. It follows that priority ought to be given to future electrification schemes for those mixed traffic lines that carry a significant volume of freight’.

WHAT’S IT WORTH?

I mentioned earlier that from now on evaluation of electrification schemes should include a ‘carbon credit’, reflecting the diesel powered train miles eliminated. But what is a tonne of CO2 worth?

Well, the government pays a £3,500 grant to encourage people to buy electric cars. Now, I am sure that this is a convenient round number acceptable to the Treasury, plus there are other subsidies for installing home chargers, but it fills the first cell on a spreadsheet.

On the basis that the petrol car that is being retired does 40 miles/ gallon and the new electric vehicle is replaced after 10 years, I make the net present value (NPV) of the reduction in CO2 £40. Applying this to the replacement of the CrossCountry Voyager fleet gives an NPV for the carbon credit for the first 10 years of around £16 million.

TECHNOLOGY

Readers may be surprised that I have not gone into the technical options for replacing residual diesel traction beyond the wires. As the opening quotation showed, the Decarbonisation Task Force, in its desire to be government-friendly, applied 80% of its effort to 20% of the problem.

That was then, when Transport Secretaries and Rail Ministers, understandably scarred by the Great Western electrification debacle, believed that bi-modes, batteries and hydrogen fuel cell power could offer the immediate benefits of electrification without the cost, disruption and political risk. Net zero carbon by 2050 has changed the equation.

Now it is only electrification that will produce the big savings. What traction runs at the fringes of the network is not a major issue and the market will provide.

If you think that complacent, consider this. Cummins, whose diesel engines probably produce more CO2 on the UK rail network than any other manufacturer, has recently acquired the shares of fuel cell manufacturer Hydrogenics. The Canadian company supplies the fuel cells for Alstom’s Coradia iLint multiple-units, now in series production.

Cummins has not fallen into the Kodak trap. The company revealed a prototype of an electric truck in 2017 and this has been followed by a number of acquisitions including battery pack specialist Brammo, Johnson Matthey’s UK automotive battery systems division specialising in electric and hybrid vehicles and Efficient Drivetrains, developer of hybrid and electric drives.

As they say on television: other hydrogen drivetrain suppliers are available. Similarly with battery power.

NOT A BREEZE

Here we come to the Task Force’s obsession with research, noting that the report was produced ‘with the support of the Rail Safety & Standards Board’. RSSB is of course the primary supplier of Bisto granules to what my colleague Ian Walmsley terms the academic research gravy train.

What is the point of spending millions on research into hydrogen fuel cell traction when, with the iLint, Alstom has hydrogen fuel cell multiple-units (HFCMU) running in service? Research funding comes from the Department for Transport, which seems unwilling to put money into the ‘Development’ that follows ‘Research’ in ‘R&D’.

My chums at Alstom and Eversholt have produced the Breeze Class 321 demonstrator (page 89, July issue). The next stage is to get it running in passenger service. Unfortunately, this is proving difficult because DfT is insisting on a full-blown business case.

Having to put a demonstrator, aimed at fulfilling political aspirations, through the appraisal system applied to commercial rolling stock acquisition is clearly a nonsense. But par for the course at New Minster House.

Meanwhile, as Lenin almost said, decarbonisation equals sustainable power plus the electrification of the whole railway.