More confirmation that politicians inhabit a parallel universe

They say of the 1960s that if you remember them you weren’t there. To judge by his comments in this year’s George Bradshaw lecture, when it comes to the 1980s, former Transport Secretary Sir Patrick McLoughlin may remember them, but must have been in a parallel universe.

RECOVERED MEMORIES

2016 LECTURE

‘Back in 1989, the railways were seen as yesterday’s industry. Remember what it was like. A difficult safety record. Managers struggling against the odds with minimal, unsustained investment. Government’s attention – elsewhere.

‘What a difference today. It is an absolute pleasure to be able to work with a confident, expanding rail industry and supply chain. Something that would have been unimaginable to many of my predecessors.’

2020 LECTURE

‘Indeed, I sometimes compare my time in the Department for Transport in the late 80s to my time there in the 2010s. In the 1980s I saw a railway in the doldrums, run by bureaucrats not entrepreneurs, dirty and unsafe, and declining in the nation’s esteem.

‘Since then, it has been utterly transformed into a growing, thriving modern railway with more than double the number of passengers.’

Sir Patrick McLoughlin, George Bradshaw lectures

DOLDRUMS

Patrick McLoughlin became a junior Transport Minister in Margaret Thatcher’s Government in July 1989, holding the position until the April 1992 general election. So how does the real world, as reported in Modern Railways, compare with his dystopian recollections?

Take ‘a railway in the doldrums’. When Sir Patrick arrived in 1989, British Rail had just enjoyed six years of uninterrupted growth, with passenger miles reaching the highest level since 1952. Following the recession at the start of the 1990s, that level of ridership would not be surpassed until 1997.

What about ‘managers struggling against the odds with minimal, unsustained investment’? Well, how about route modernisation and electrification of the East Coast main line?

Presumably the inaugural 3hr 29min London to Edinburgh record run in 1991 somehow passed him by. And wouldn’t you have expected a true-blue Tory to take any opportunity to celebrate the fact that more route miles of electrification were commissioned during the blessed Hilda Margaret’s reign than any other administration before or since?

MISSED

His attention must have been elsewhere, since he also missed the re-equipment of the passenger and freight rolling stock fleets – with 4,000 passenger vehicles delivered in the decade before privatisation. Or what about the birth of the Digital Railway, with the first Integrated Electronic Control Centre at Liverpool Street going live as he settled into his ministerial office?

Then there’s total route modernisation of the Chiltern line and (I think you’ve made your point – Ed). Can I just point out that Chris Green and his fellow Sector Directors were far more entrepreneurial than the bureaucrats in charge of franchising today? (Oh, all right then – Ed.)

COSTS

Anyway, with my blood well and truly up, I thought it might be apposite to update my comparison of BR’s cost to the Government with today’s railway. This always goes down well with the defenders of Sir Patrick’s ‘growing, thriving modern railway with more than double the number of passengers’.

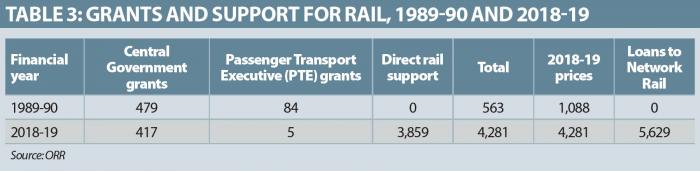

Table 3 shows the base data from the ORR website. You may be wondering why I chose 1989-90 rather than the elegance of a 20-year interval.

Simply because British Rail repaid borrowing to the Government in 1988-89, to the tune of £340 million at 2018-19 prices. I thought it a trifle unsporting to take advantage of that bounty.

So, today’s railway costs the taxpayer roughly four times as much as Bob Reid’s business-led railway needed in its pomp. But, of course, this doesn’t allow for the fact that today’s railway is much busier.

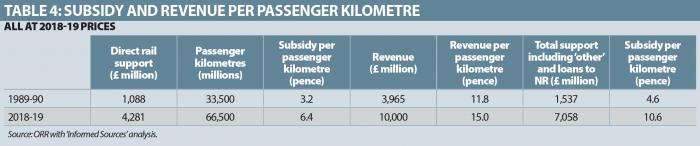

Hence Table 4 adds ridership in passenger kilometres. As you can see, subsidy per passenger kilometre has roughly doubled.

So what about revenue? At today’s prices, passenger revenue is 125% up on 1989-90. When corrected for ridership, revenue per passenger kilometre is up 27%.

A final statistic is that the rolling stock fleet has not increased significantly. In 1989-90 British Rail was running 12,500 vehicles. Today the total is around 14,000 – a 12% increase.

For completeness I have added separate columns including the ‘other support’ category in the BR data and loans made to Network Rail in 2018-19. Call me a cynical old curmudgeon, but I can’t see these loans being repaid any-day soon. In this case the subsidy per passenger kilometre is still roughly double.

DISECONOMIES OF SCALE?

For an industry with a high fixed-cost base, essentially the same assets and growing demand, you would expect the unit cost of production, and thus subsidy, to fall as throughput increased and spare capacity was filled. You would have to be really clever to reorganise such an industry in such a way that when its throughput has doubled over 20 years, and revenue more than doubled, so has the unit cost in terms of subsidy needed.

No doubt the privatisation ‘ultras’ at the Rail Delivery Group have a perfectly good explanation for why this financial situation is perfectly normal for the best of all possible railways. No doubt all will be explained in next month’s letters page.

By chance, recently I came across this quote from Richard Bowker, the Chairman of the Strategic Rail Authority, in 2002. That was the time when I was pointing out that infrastructure project costs had risen to triple those under British Rail. ‘Personally, I couldn’t care less what it cost BR. All that matters is what it costs now and what we have to do to get it under control’, Sir Richard told me.

To mix a metaphor, not paying sufficient attention to pre-privatisation yardsticks has seen the boiling frogs come home to roost.