Informed Sources

Can the Transport Secretary revive the walking dead?

In the April 2018 column I reported on the rising number of ‘zombie franchises’, train operating companies that were continuing to meet their inancial obligations to the Department for Transport while losing money on their passenger services. While commercially dead, they were drawing down support from their parent companies to remain inancially viable.

But since they were separate limited liability companies, once the Parent Company Support (PCS), committed in their franchise agreements, ran out, they would have to default and lose the franchise.

The irst of this wave of zombie franchises was Virgin Trains East Coast (VTEC), now taken over by the Department for Transport’s Operator of Last Resort (OLR) London North Eastern Railway (LNER).

It is worth noting that LNER is an autonomous arm of government with its own Accounting Oicer, which means, for example, that while it will show its new business plan to DfT it is not dependent on ministerial approval. Let’s see how that pans out when it comes to written parliamentary questions.

LOSSES

Back in April, in addition to VTEC, ScotRail had reported a loss of £5 million and had also secured a £10 million loan from parent company Abellio. Serco had also categorised its Caledonian Sleepers franchise as an onerous contract following a £30.6 million loss.

Statutory reports and accounts are invaluable in detecting incipient zombie franchises.

In the case of Serco, Caledonian Sleepers was shown as the largest of the group’s onerous contract provisions at £44 million.

Fortunately, from 2020 the franchise agreement provides ‘a mechanism’ that requires Transport Scotland to bear 50% of contract losses. And, according to Serco, from 2022 the deal can be altered to result in a ‘positive proit margin’.

EAST ANGLIA

In September, Abellio East Anglia iled its Report & Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2018 and it was clear we had another zombie franchise on our hands. Despite underlying revenue growth of 5.3%, a previous year proit before taxation of £19.4 million had turned into a £1.1 million loss.

Note that the previous short accounting ‘year’ had run from the start of the current franchise in October 2016 to March 2017.

If the loss was bad news, tucked away on page 30 of the Accounts was the revelation that on 31 January 2018 the franchise had drawn down £30 million of its PCS – £18 million from Netherlands Railways (NS) and £12 million from joint franchisee Mitsui & Co.

These loans are repayable in two equal instalments in December 2020 and December 2021.

This was followed in August by a further £30 million from NS and £20 million from Mitsui. Repayment, in two equal instalments, falls due in December 2023 and December 2024. The rate of interest is 8%.

Abellio’s total PCS facility is set at £271.8 million. Note that the sums drawn down are to be paid back in stages by 2024.

EMPLOYMENT

But all is not quite as it seems. Previously franchises had been protected from the impact of exogenous economic forces by the Cap & Collar mechanism. If revenue fell below forecast, the loss was capped in stages, with up to 80% of the lost revenue being covered by DfT. Should revenue beat forecast, however, an increasing share of the gain was ‘collared’ by the taxpayer.

Following the Inter-city West Coast franchise procurement scandal, new-broom Franchise Director Peter Wilkinson went back to irst principles of protecting franchise bidders against the revenue risks inherent in committing to long-term ridership and revenue forecasts for an industry dependent on the state of the economy. Two indices would be used to replace Cap & Collar, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Central London Employment (CLE).

There was a fascinating chart in British Rail’s Network SouthEast (NSE) days that plotted CLE and NSE ridership against time. And the two curves rose and fell in almost complete synchronicity.

PROTECTION

Thus the East Anglia franchise agreement includes provision for both GDP and CLE adjustments in order to share revenue risk. I have read the respective sections in the franchise agreement and think I could understand the formulae for the two mechanisms if I had a spare day, but forgive me if I don’t bother you with it for this month.

In the case of the CLE, the franchise agreement says that the Annual Population Survey (APS) workplace analysis, published by the Oice of National Statistics (ONS), should be used for the CLE mechanism using data from 10 London Boroughs – Camden, City of London, Hackney, Islington, Kensington & Chelsea, Lambeth, Newham, Tower Hamlets, Southwark and Westminster.

However, according to Abellio ‘a signiicant and unexpected upward revision to CLE reported actuals was seen for 2015-16, 2016-17 and 2017-18’ which was not in line with real world commuter travel growth trends. Abellio is arguing that somewhere along the line the historic link between CLE and commuter ridership has broken down. As a result, the CLE formulae were coming up with revenue share payments to DfT that were not covered by revenue growth on the real railway.

Abellio made provision of £1 million for its initial half-year to 31 March 2017, pending a review of the ‘unintended consequence’ due to the broken link. However, DfT decided to enforce the payment mechanism – hence the loss.

In a statement Abellio told me: ‘It is now widely accepted that CLE is a lawed mechanism that does not deliver on the intended aims.

We are therefore working with the DfT to develop and implement more efective risk sharing models’.

SWR TOO

Abellio calls in aid the claim that rail franchises let after Greater Anglia do not have the same arrangement in their franchise agreements. This is not quite true.

The East Anglia franchise agreement is dated August 2016.

The South Western franchise agreement, which is dated April 2017, replicates the GDP and CLE sections in the East Anglia document, although Hackney and Tower Hamlets are missing from the list of boroughs providing the CLE data.

So CLE lives on and good luck to Abellio with the renegotiation. But also commiserations to SWR franchisees First and MTR if they are caught in the same CLE anomaly on top of their other problems.

Meanwhile, I am assured that East Anglia revenue for 2018-19 is ‘on target’. With the arrival of the new Bombardier and Stadler rolling stock leets ‘from the middle of next year’ Abellio expects to meet its growth targets.

NORTHERN

Two phrases beloved of the mainstream media when it comes to franchises, but which are deprecated in this column, are ‘bail out’ and ‘stripped’, as in ‘stripped of franchise’. The latest ‘bail out’ shock horror victim is Northern.

It is unfair to rank Northern among the living dead battering on the Department for Transport’s front door. Rather, they are the walking wounded brought in after a ‘blue-on-blue’ friendly ire incident from DfT’s own agency, Network Rail. Network Rail’s failure to deliver the Manchester-Bolton electriication in time for the May 2018 timetable change and the ensuing collapse of train service performance will have cost Northern dear, both in income and reputational damage. Schedule 8 payments are unlikely to have relected the full cost.

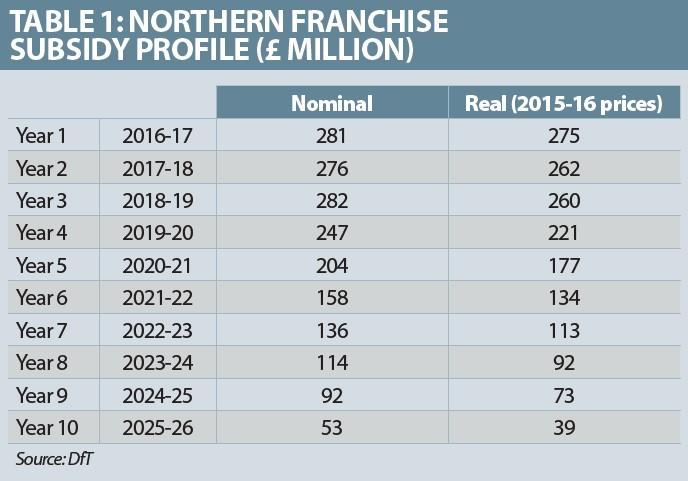

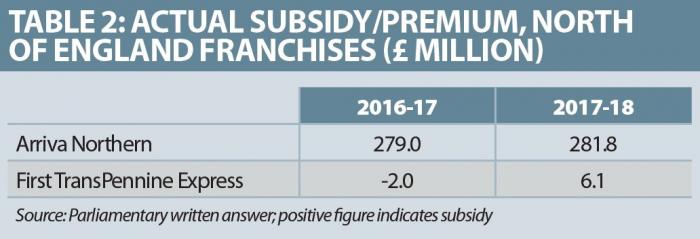

Table 1 shows the subsidy proile for the Northern franchise. Note that the real payments are at 2015-16 prices. Nominal payments include an allowance for inlation.

Table 2 shows the actual payments to date. As you can see, the expected fall in subsidy in the second year of the franchise has become a slight increase. Clearly, in addition to the immediate loss of revenue, the growth of ridership and revenue on which the falling subsidy proile was predicated will not now start until later in the franchise and from a lower base. This will shift the subsidy proile to the right.

When the story ran in The Daily Telegraph, a Northern spokesman noted that the franchise ‘has faced a number of exceptional circumstances (and) we are in constant dialogue with DfT’. I bet!

TRUMPETING

Exhibit A in the Rail Delivery Group’s (RDG) trumpeting of the triumph of privatisation is that a subsidy of £2 billion in 1996-97 has become a net premium today. Given that this column has explained in detail (excruciating detail! – Ed) that this ignores the direct grant to Network Rail, you have to admire RDG’s nerve in repeating this canard (is that French for ib? Ed).

But the net premium is conirming that franchising is in trouble. It fell from £776 million in 2016-17 to £223 million in 2017-18. A drop of 71.3%. So, apart from risking the creation of more zombies, why is DfT continuing with the procurement of three franchises, two distinctly dodgy and one away with the fairies? And that is before the known unknown of the Williams Review recommendations.

REVIEW

Announcing the Review in September, the Transport Secretary noted that his department had reviewed all ongoing franchise competitions in the context of the Rail Review. ‘Due to the unique geographic nature of the Cross Country franchise, which runs from Aberdeen to Penzance and cuts across multiple parts of the railway, awarding this franchise in 2019 could impact on the Review’s conclusions’.

As a result Arriva will retain the franchise, presumably under a new direct award, ‘with options beyond this to be considered in due course’. It’s worth noting that in a recent response to a Parliamentary question on the timeframe for the procurement of new rolling stock on the Cross Country franchise, DfT’s answer was that ‘the timeframes for the new franchise are yet to be determined’ and that ‘it would be for an operator of the franchise to establish their speciic rolling stock requirements’. Tough luck if you don’t like overcrowded Voyagers.

SUNK COST

Meanwhile, other ongoing franchise competitions ‘are continuing as planned’. These are South Eastern, East Midlands and the West Coast Partnership, which will combine running Inter-city West Coast with the introduction and initial operation of High Speed 2 services.

But why bin only Cross Country when South Eastern has already had to be rebid and East Midlands has more uncertainty than Heisenberg could have imagined? And not only that, even Transport Secretary Chris Grayling has declared that franchising has reached the end of the road.

I suspect that in the case of Cross Country, Williams provided an opportunity to hide the embarrassment that only one operator had shown any interest in bidding.

For the others, look at Table 3.

Having spent £21.7 million on consultants supporting procurement of the three franchises, and with ‘only’ another £6.3 million to inish the job, you can see that ‘press on regardless’ might be the Department’s reaction. Meanwhile, in the real world £28 million would buy you 5x4-car EMUs.